—By Sister Catherine Marie, O.P.

Compare for a moment these two lines spoken by women:

Compare for a moment these two lines spoken by women:

“Behold the handmaid of the Lord; be it be done to me according to Thy word” (Lk 1:38).

“Rise and Roar.”

The first is, of course, our Blessed Mother, and the second is a phrase chanted at the 2020 Women’s March. The first is the model for women in religious life. The second, we are told, is what will bring women freedom and empowerment. How can these two views of womanhood be reconciled? How can women who chant the second phrase, live the first? In short, they cannot.

There are many reasons why Catholicism, let alone religious life, and feminism cannot coexist. But first, let us make clear, by this I do not mean that men and women are not both of equal value in the dignity of being created by God. Instead, feminism means trying to make women something they were not created to be, and thus, makes them less than who they really are.

One of the most fundamental reasons feminism and Catholicism are opposed is that its roots stem from Communism. The proponents of modern feminism are open (sometimes) about this truth. Ellie Mae O’Hagan, freelance journalist, insists that only changes such as socialism or Communism can bring about gender equality. She quotes the Bolshevik revolutionary Inessa Armand, “If women’s liberation is unthinkable without Communism, then Communism is unthinkable without women’s liberation.”1

Another major reason that feminism and Catholicism cannot coexist is that it denies the virtues that are inherent to women. Alice von Hildebrand, an expert on the Catholic perspective of womanhood, gives us some clues in this matter. “They [women] let themselves become convinced that femininity meant weakness. They started to look down upon virtues —such as patience, selflessness, self-giving, tenderness—and aimed at becoming like men in all things.”2 Catholic femininity does not equal weakness. Virtue is not a weakness, but a power. We have only to look at the many Catholic female saints and to our Blessed Mother to see this truth.

Another major reason that feminism and Catholicism cannot coexist is that it denies the virtues that are inherent to women. Alice von Hildebrand, an expert on the Catholic perspective of womanhood, gives us some clues in this matter. “They [women] let themselves become convinced that femininity meant weakness. They started to look down upon virtues —such as patience, selflessness, self-giving, tenderness—and aimed at becoming like men in all things.”2 Catholic femininity does not equal weakness. Virtue is not a weakness, but a power. We have only to look at the many Catholic female saints and to our Blessed Mother to see this truth.

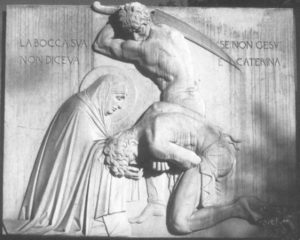

St. Catherine of Siena in her early days remained humble and hidden in the small room of her parent’s home, in prayer and in service of her family. Yet, she was one of the strongest female saints that the  Church has ever seen. One day she was drawn out of her little room by a tumult outside. She saw a man had been taken into custody for a crime. He was sentenced to death. It is through her hiddenness in prayer and service that she was able to hear the voice of God, to respond in feminine compassion, and go to this man. She spent the night talking with him and praying with him. By the morrow, this hardened sinner was completely converted, wanting his “Mama,” Saint Catherine, with him at the scaffold. As his head was lopped off, she received it into her lap. Hardly a weak woman!

Church has ever seen. One day she was drawn out of her little room by a tumult outside. She saw a man had been taken into custody for a crime. He was sentenced to death. It is through her hiddenness in prayer and service that she was able to hear the voice of God, to respond in feminine compassion, and go to this man. She spent the night talking with him and praying with him. By the morrow, this hardened sinner was completely converted, wanting his “Mama,” Saint Catherine, with him at the scaffold. As his head was lopped off, she received it into her lap. Hardly a weak woman!

Look also at how Our Lady stands at the foot of the cross of her Son. Her strength is unmatched by the men who fled from Christ in His hour of need, but it is still a woman’s strength. Her suffering with her Son does not end in despair or the sorrows of Good Friday, but turn into the hymn Regina Caeli on Easter Sunday. Our Lady is receptive, humble, thoughtful, full of grace, and yet, “as terrible as an army with banners” (Sg 6:10), and “crowned with twelve stars and with the moon beneath her feet” (Rev 12:1). She is the most glorious of all creatures, and the fruit of her womb is the Son of God.

Look also at how Our Lady stands at the foot of the cross of her Son. Her strength is unmatched by the men who fled from Christ in His hour of need, but it is still a woman’s strength. Her suffering with her Son does not end in despair or the sorrows of Good Friday, but turn into the hymn Regina Caeli on Easter Sunday. Our Lady is receptive, humble, thoughtful, full of grace, and yet, “as terrible as an army with banners” (Sg 6:10), and “crowned with twelve stars and with the moon beneath her feet” (Rev 12:1). She is the most glorious of all creatures, and the fruit of her womb is the Son of God.

With feminism, there is a strength seen in their fighting for certain issues, but one that in its suffering and sacrificing for a cause often ends, not in glory, but in loneliness. This is seen in the feminist Simone de Beauvoir who says, “I am too intelligent, too demanding, and too resourceful for anyone to be able to take charge of me entirely. No one knows me or loves me completely. I have only myself.”3 There is a grasping for power and independence, unlike the obedience of faith seen in Mary. This grasping is very reminiscent of the grasping of Eve in the garden. And that fruit of success and independence that feminists reach for ends similarly. In trying to find the goddess within, they find inside what we all do: our own brokenness, but without the God who can heal it.

As we know, grace builds on nature. If young women have been raised with feminist values, even if they are still able to hear the call to religious life, they most likely will not have the building blocks necessary to make vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. Regarding the vows, a brief look at each, shows how the evangelical counsels cannot be reconciled with the goals of feminism.

In chastity, “the bridal relationship of each soul to God, the feminine aspect of the whole people of God before His gaze in all salvation history, is strikingly imaged in the virginally consecrated religious woman.”4 A woman gives all of herself to the Church, and herself becomes an image of the Church, which is the Bride of Christ. “The virgin who consecrates herself to God in total donation is not and cannot remain barren. She, too, is called to be called mother, but her motherhood is of a spiritual nature.”5 Contrast this with a statement by feminist Ti-Grace Atkinson: “The struggle between the liberation of women and the Catholic Church is a struggle to the death.”6 Feminists see the Church as a patriarchal structure that must be defeated. With this mindset one could never be an image of the Bride of Christ, the Church.

In chastity, “the bridal relationship of each soul to God, the feminine aspect of the whole people of God before His gaze in all salvation history, is strikingly imaged in the virginally consecrated religious woman.”4 A woman gives all of herself to the Church, and herself becomes an image of the Church, which is the Bride of Christ. “The virgin who consecrates herself to God in total donation is not and cannot remain barren. She, too, is called to be called mother, but her motherhood is of a spiritual nature.”5 Contrast this with a statement by feminist Ti-Grace Atkinson: “The struggle between the liberation of women and the Catholic Church is a struggle to the death.”6 Feminists see the Church as a patriarchal structure that must be defeated. With this mindset one could never be an image of the Bride of Christ, the Church.

In poverty, we rely on the providence of God to supply for our needs, and freely divest ourselves of those things we do not need, reflecting that Christ received all from the Father and returns all to His Father Who loves Him infinitely. The goal of feminism is to gain, not to give. Keisha Blair, an author on the topic of wholistic health, stated that financial empowerment is the new feminism.7

The surrender of ones will in the vow of obedience, is self-evidently opposed to the goals of feminism, as it thrives on disobedience. Obedience is of course the most difficult of the vows because it is  the greatest gift of self. It is the paradox of faith that one must lose one’s life to save it. When young women contact vocation directors or novice mistresses of religious orders, often they ask if there is some guarantee that their studies or profession will be used in their vocation. The answer to that is to look to Mary: how much more gifted she was than any of us, yet she gently bowed her head to God’s will, not asking for any guarantees that her gifts and talents would be used as she liked. She saw many trials and sorrows, but, because of her obedience, was exalted by God above the angels and crowned as Queen of Heaven and earth.

the greatest gift of self. It is the paradox of faith that one must lose one’s life to save it. When young women contact vocation directors or novice mistresses of religious orders, often they ask if there is some guarantee that their studies or profession will be used in their vocation. The answer to that is to look to Mary: how much more gifted she was than any of us, yet she gently bowed her head to God’s will, not asking for any guarantees that her gifts and talents would be used as she liked. She saw many trials and sorrows, but, because of her obedience, was exalted by God above the angels and crowned as Queen of Heaven and earth.

Fortunately, with the rise of militant feminism, there is also a new generation of young Catholic women who are sharing the Gospel message of a return to authentic Catholic femininity. Yet, young women need to grow in self-knowledge, that having been reared in a culture where the errors of feminism are sounded like a bull horn at us from nearly every angle, some of these ideas have taken hold in us unawares. Catholic women, to find their vocation, must, like Mary, ponder all these things in their hearts, and grow in feminine virtues. Mary is the antidote, because “she surrendered every piece of herself to God the Father as a beloved daughter.”8

To say, “just imitate Mary,” can seem like a mountain impossible to climb. But in the spiritual life, one does not grow in virtue by dispelling all vice at once. No, “you drive out darkness by filling the room with light. If you wish to fill a glass with water, you do not first expel the air; you expel the air by pouring in water. In the moral life, there is no intermediate state of vacuum possible in which, having driven out evil, you begin to bring in good. As the good enters, it expels the evil.”9 So, to imitate Mary’s virtues, we start in little ways, especially by spending time with her in prayer, and slowly our Mother will help to increase her virtues within us.

With God, we know all things are possible, and we know that He has a more beautiful plan for our femininity if we heed Him. We cannot improve upon His plan for us! And in living that plan, a woman who gives herself freely to religious life, becomes an eschatological sign of the kingdom of God. Our world needs, maybe now more than ever, this beautiful witness. So, “Arise, make haste, my love, my dove, my beautiful one, and come” (Song of Songs 2:10).

- Ellie Mae O’Hagan, The Guardian March 2019; “Feminism Without Socialism Will Never Cure Our Unequal Society,”

- Alice von Hildebrand, The Privilege of Being a Woman

- Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex

- Mother Mary Francis, P.C.C., Chastity, Poverty, and Obedience: Recovering the Vision for the Renewal of Religious Life

- Alice von Hildebrand, The Privilege of Being a Woman

- Jane Stannus, “There is no Catholic Feminism,” Jan. 29, 2020, Crisis Magazine

- Keisha Blair, “Financial Empowerment is the New Feminism – Here’s Why,” Jan.18, 2020, Observer Daily Newsletter

- Carrie Gress, Anti-Mary Exposed: Rescuing the Culture from Toxic Feminity

- Basil W. Maturin, Christian Self-Mastery

Sr. Catherine Marie Kauth, OP, is the Vocation Director for the Dominican Sisters of Hawthorne.