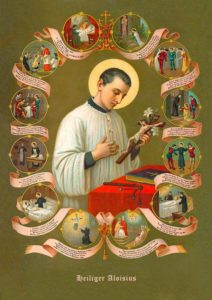

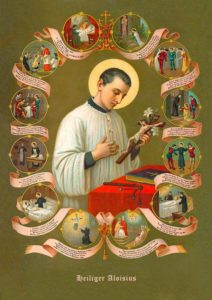

Now some insights into Aloysius’ spirituality. To the one virtue which the Church has chosen, and on account of which has chosen him ‘the universal patron of youth’, was his chastity. All the evidence we have indicates that he had very strong sexual passions. We know that from his own writing; we know that from people who knew him and we know that from what is called penance from one view-point, what is really, you might say ‘preventive austerity’ from another. He simply believed that unless he mortified his body, and I didn’t tell you one tenth of what he did, he just would not get that passion under control. The lesson for us, in a sex-mad world, is obvious. You do not control that passion without mortification, you just don’t. As a result, the Church has held him up as a model of what even the most passionate personality can achieve, always with God’s grace, but not as we’ve said, more than once. We may not be able to, given our temperament of the circumstances in which we are living, we may not be able to cope with temptation–we need grace, very well, how do you get the grace? –through prayer and mortification. And Christ’s words, remember? about a certain demon, not being able to be driven out except, remember? through penance. Well, it’s a non-title to give the devil, but, he is the demon of lust; though being without a body himself, he knows, he knows, how by stirring this passion, he can lead people into any kind of sin. That’s the first and towering lesson of the life of St. Aloysius.

Now some insights into Aloysius’ spirituality. To the one virtue which the Church has chosen, and on account of which has chosen him ‘the universal patron of youth’, was his chastity. All the evidence we have indicates that he had very strong sexual passions. We know that from his own writing; we know that from people who knew him and we know that from what is called penance from one view-point, what is really, you might say ‘preventive austerity’ from another. He simply believed that unless he mortified his body, and I didn’t tell you one tenth of what he did, he just would not get that passion under control. The lesson for us, in a sex-mad world, is obvious. You do not control that passion without mortification, you just don’t. As a result, the Church has held him up as a model of what even the most passionate personality can achieve, always with God’s grace, but not as we’ve said, more than once. We may not be able to, given our temperament of the circumstances in which we are living, we may not be able to cope with temptation–we need grace, very well, how do you get the grace? –through prayer and mortification. And Christ’s words, remember? about a certain demon, not being able to be driven out except, remember? through penance. Well, it’s a non-title to give the devil, but, he is the demon of lust; though being without a body himself, he knows, he knows, how by stirring this passion, he can lead people into any kind of sin. That’s the first and towering lesson of the life of St. Aloysius.

That chastity is not easily preserved in any age and in our day, is humanly impossible without grace merited through prayer and penance. A good reason, a very good reason, for becoming a religious these days, I mean, of course, a good religious, a real religious, is to preserve oneself from the lust that we breath in a country like ours like the atmosphere.

Second feature of his spirituality. His profound humility shown in the fact that as you know in certain cultures, notably the Italian and Spanish nobility, is highly prized. And after four hundred years, for example, in Latin America, the cleavage between, call them the nobility, and the rest of the people, Aloysius, under divine inspiration from early boyhood, recognized that if he is to even save his soul, he cannot pride himself on his rank or social state. In the United States we don’t have, I suppose I can say, “thank God”, nobility. We don’t have a lady this and a sir that or counts and countesses, but, my friends, we sure have status. The books that I’m not recommending to your reading, but just to know that it exists. It’s a good book to read, called “Status Secrets” by Vance Packard. In the United States, Packard describes with great detail how status conscious Americans are. I live on 83 and Park Ave. All I have to do is walk up Park Ave. to 96th Street and then it’s a different world. In other words, you might say the barbarians of New York live beyond 96th. Where people live, how they dress, even the names of the streets, ‘Aw, you can live on such and such a drive or such and such a lane or you have not a cheap, pardon me, Chevrolet or Ford, but a Buick or a Cadillac. Aloysius hated pretense–a lesson for everyone of us–putting on, and let me tell you, this has infested every rank and every state of life. I won’t dare identify the diocese, but I called up … I was in the city on some great problem affecting the large community of the diocese and I wasn’t just a private individual because I do work for the Congregation for Religious, so I called up to make an appointment with a Vicar for religious in that diocese and he invited me, 12 o’clock noon, I thought to myself, “how kind of him, we’ll have lunch together”, so I showed-up at the Chancery, few minutes before 12 and a receptionist said, ‘sit down’ so I sat down. And a telephone call from the priest was “Vicar, call the office”, he was in the building, ‘would you tell Father to wait while I have my lunch’. I waited over an hour. He came back smiling. All I can tell you, it took a lot of grace, but I smiled, too. He wanted to make sure I knew who was in charge, because he knew the message that I had to share with him would somehow touch on his authority. That’s the second feature of Aloysius’ spirituality–a humility without pretense and he didn’t have to pretend because he was of the highest nobility.

Third feature of his spirituality, we may call it casually, penance, but it is much more refined. Under divine guidance, Aloysius recognized that we all have powerful drives in our fallen nature, called the ‘capital sins’, the more sophisticated name is our concupiscence. We all have these drives–there are seven. You know them by heart, don’t you? you know them by memory, don’t you? places g … well, this is an insight into the meaning of penance that only a person as totally innocent as Aloysius could teach us … one reason he was canonized. For even though we have not personally sinned, we commonly and correctly associate doing penance for our own past mistakes. In Margaret of Cortona, all right, she had a sinful past, and Augustine, you better believe it, had a sinful past but not Aloysius. So what’s all this penance about. There are a few things I will share with you during these conferences on the Jesuit saints, more important than this one. The insight that he gave the Church was that even though we have not personally sinned, either we do, and the word is violence to our sinful nature or concupiscence will do violence to us. Now in some people, they are just stronger than in others. Mothers tell me, they can tell when, for example, a child, a girl of three … “Father” the mother tells me, “Mary is going to have trouble with humility for the rest of her life.” Have you seen it in youngsters? or temper, or, and this is the easiest, sloth. We all have these drives, some are stronger than others, depending on who the person is and how much we have given in to a particular tendency. With Aloysius, it was lust, he knew it and in order to teach the world the need for penance, not just to expiate sins committed but in order to master our sinful desires what we still call penance, is something that we should all learn from Aloysius to practice, to ask ourselves, what is my predominant passion? and then, what am I doing? Ignatius famous phrase ‘Hacer contra’ act against, do the opposite of that which you have a tendency to do.

Third feature of his spirituality, we may call it casually, penance, but it is much more refined. Under divine guidance, Aloysius recognized that we all have powerful drives in our fallen nature, called the ‘capital sins’, the more sophisticated name is our concupiscence. We all have these drives–there are seven. You know them by heart, don’t you? you know them by memory, don’t you? places g … well, this is an insight into the meaning of penance that only a person as totally innocent as Aloysius could teach us … one reason he was canonized. For even though we have not personally sinned, we commonly and correctly associate doing penance for our own past mistakes. In Margaret of Cortona, all right, she had a sinful past, and Augustine, you better believe it, had a sinful past but not Aloysius. So what’s all this penance about. There are a few things I will share with you during these conferences on the Jesuit saints, more important than this one. The insight that he gave the Church was that even though we have not personally sinned, either we do, and the word is violence to our sinful nature or concupiscence will do violence to us. Now in some people, they are just stronger than in others. Mothers tell me, they can tell when, for example, a child, a girl of three … “Father” the mother tells me, “Mary is going to have trouble with humility for the rest of her life.” Have you seen it in youngsters? or temper, or, and this is the easiest, sloth. We all have these drives, some are stronger than others, depending on who the person is and how much we have given in to a particular tendency. With Aloysius, it was lust, he knew it and in order to teach the world the need for penance, not just to expiate sins committed but in order to master our sinful desires what we still call penance, is something that we should all learn from Aloysius to practice, to ask ourselves, what is my predominant passion? and then, what am I doing? Ignatius famous phrase ‘Hacer contra’ act against, do the opposite of that which you have a tendency to do.

Fourth feature of his spirituality. Aloysius had a profound understanding of the gravity of sin. In his own life, in the life of others and in how dreadful a thing it is to offend the good God. If there is one mystery of our faith that needs strengthening in these days, it is the fact of sin. Who talks about it? He was not a theologian, but one of the ranking American psychiatrists who wrote a book not too long ago on “What ever happened to sin?” People have simply lost their sense of guilt.

Fifth feature. Already from childhood, Aloysius looked forward to going to Heaven, the mystery of Heaven. No doubt one reason that he performed extraordinary penance, and that remember in addition to all of his physical disabilities which he already experienced from childhood, one reason was that he just looked forward to a day and all of this would end. No wonder when he caught the plague in Rome, from which he briefly recovered then shortly after got a fever and died, he confessed impatience with wanting to die. It wasn’t death that he welcomed, it was the aftermath of death, namely Heaven. May I recommend a daily looking forward to Heaven and to ask God to give us some foretaste of what awaits us. It will make this world, seem by comparison, very cheap and dreary, indeed.

Another feature of Aloysius spirituality is charity in the practice of mercy so much so that we can call him a ‘martyr of charity.’ Sometime when we read Christ’s statement which he made by our loving our neighbor even to laying down our life for the neighbor, we don’t really mean this, but, we think, well, it must be some theological exaggeration, Christ didn’t really mean it. He not only meant it, He lived it, or you could make a transitive verb-He died it. That’s what the crucifixion is all about. One meaning of Calvary that can be lost on us–this is a voluntary sacrifice of His life as an act of charity. Most of us find enough difficulty, I don’t say in dying for people, but in living with people. I get some idea of how this charity can be very costly. If in God’s providence He gives us the opportunity of laying down literally our lives for another person, God be praised. Whom is the Holy Father canonizing this year who is a martyr of charity, Maximillian Kolbe. Another one, Aloysius. Charity, in other words, means not only doing good, but giving up self including the dearest possession we have, naturally speaking, our lives.

And finally, Aloysius spiritual joy. As we look at the short life of Aloysius, depending on the person’s view point, it may seem oppressive, it shouldn’t be, but, in modern jargon, it has so much (pardon the expression) so much of the negative, you know, penance, mortification, sin–and a world that has gone mad, drunk with sin, doesn’t realize that already this side of eternity, we are to be an Aloysius was literally; we are to be, if it is God’s will, ecstatically happy of that. We are not to be sad. We are not, God forbid, to be unhappy. The secret, and what an open secret it is in the life of Aloysius, the secret is to find the happiness in the right place. That’s all, yes, but that’s everything. In other words, as a closing observation, Aloysius showed that’s why the Church canonized him, that when Christ gave us the eight Beatitudes, which are eight promises of happiness, He meant it. The condition for being happy, well, that’s part of the Covenant, that’s what we do, but if we do our part, God comes through.

Saint Aloysius, pray for us. In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.

Like this:

Like Loading...

St. Ignatius of Loyola learned from the lives of the saints, and the concrete witness of their lives transformed him. He saw that Christ was the center of their particular lives, and he started to see the narrative of his own life in such a way. In The Grammar of Assent, Bl. John Henry Newman distinguishes between notional assent and real assent. In a nutshell, notional assent is the acknowledgement we give to the truth of abstract propositions. It is not an assent grounded in concrete experiences, and it often makes little difference in the way we live. One can see this in arguments for the existence of God. Often times, the argument from contingency doesn’t transform us. However, as Newman points out, the argument from conscience does have this effect. Many have the real experience of the pangs of conscience, and the intuition of a supreme moral authority. We sense this to be the voice of God. Newman says that religion must have both. However, if you want to transform men real assent is necessary. Newman says, “Many a man will live and die upon a dogma: no man will be a martyr for a conclusion…No one, I say, will die for his calculations: he dies for realities.” Real assent is grounded in real objects that have a force on a person unlike notional assent. It is grounded in experience. As a Brit, Newman resisted the abstractions of continental philosophy. However, he didn’t lead us down the equally abstract empiricism of Hume but to the true experience we all have, i.e. the intuition of the real world and the sense of God that is written on our hearts. Ignatius is an example of the transformation real assent can influence not only one life but the whole world.

St. Ignatius of Loyola learned from the lives of the saints, and the concrete witness of their lives transformed him. He saw that Christ was the center of their particular lives, and he started to see the narrative of his own life in such a way. In The Grammar of Assent, Bl. John Henry Newman distinguishes between notional assent and real assent. In a nutshell, notional assent is the acknowledgement we give to the truth of abstract propositions. It is not an assent grounded in concrete experiences, and it often makes little difference in the way we live. One can see this in arguments for the existence of God. Often times, the argument from contingency doesn’t transform us. However, as Newman points out, the argument from conscience does have this effect. Many have the real experience of the pangs of conscience, and the intuition of a supreme moral authority. We sense this to be the voice of God. Newman says that religion must have both. However, if you want to transform men real assent is necessary. Newman says, “Many a man will live and die upon a dogma: no man will be a martyr for a conclusion…No one, I say, will die for his calculations: he dies for realities.” Real assent is grounded in real objects that have a force on a person unlike notional assent. It is grounded in experience. As a Brit, Newman resisted the abstractions of continental philosophy. However, he didn’t lead us down the equally abstract empiricism of Hume but to the true experience we all have, i.e. the intuition of the real world and the sense of God that is written on our hearts. Ignatius is an example of the transformation real assent can influence not only one life but the whole world.