The following is an interview with Cristina Borges, author of the book: “Of Bells and Cells: The World of Monks, Friars, Sisters and Nuns“

What prompted you to write a book for the young reader about religious life?

Once I was having a conversation with a teenage girl whom I knew was a practicing Catholic. I mentioned something about St. Therese of Lisieux, and I noticed by her reaction that she had never heard of her. I remember saying, “You, know the Carmelite saint, [etc]?” to which I received an even more perplexed blank stare. Here was this very nice young lady from a good Catholic family, who went to Mass every Sunday, and she had never heard of Carmelites or the Little Flower! I thought to myself, “How deprived! A Catholic not knowing what Carmelites are.” And through my mind, in a flash, passed all the wealth that religious orders and their saints have enriched humanity with. Right then and there I decided: “I’m going to write a book about religious orders for children!” But when I sat down to it, I realized I couldn’t begin writing about the history, charisms, saints, or spiritual and societal impact of the key religious orders without assuming some pre-knowledge of what religious life is. So out came a book about the basics of religious life.

Once I was having a conversation with a teenage girl whom I knew was a practicing Catholic. I mentioned something about St. Therese of Lisieux, and I noticed by her reaction that she had never heard of her. I remember saying, “You, know the Carmelite saint, [etc]?” to which I received an even more perplexed blank stare. Here was this very nice young lady from a good Catholic family, who went to Mass every Sunday, and she had never heard of Carmelites or the Little Flower! I thought to myself, “How deprived! A Catholic not knowing what Carmelites are.” And through my mind, in a flash, passed all the wealth that religious orders and their saints have enriched humanity with. Right then and there I decided: “I’m going to write a book about religious orders for children!” But when I sat down to it, I realized I couldn’t begin writing about the history, charisms, saints, or spiritual and societal impact of the key religious orders without assuming some pre-knowledge of what religious life is. So out came a book about the basics of religious life.

It is beautifully illustrated …

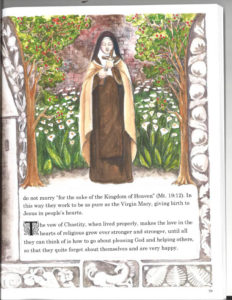

Yes, and that is really a crucial factor. I wrote the text very deliberately in a simple and methodical way, having in mind that illustrations would do the work of bringing the text to life—that they would bring out the poetry behind the text and actually complement the meaning of the letter. I had set ideas of how each page should be illustrated and made some very rough sketches. But it took me 14 years to find the illustrator who understood what I was trying to do and had the talent and ability to execute it.

Yes, and that is really a crucial factor. I wrote the text very deliberately in a simple and methodical way, having in mind that illustrations would do the work of bringing the text to life—that they would bring out the poetry behind the text and actually complement the meaning of the letter. I had set ideas of how each page should be illustrated and made some very rough sketches. But it took me 14 years to find the illustrator who understood what I was trying to do and had the talent and ability to execute it.

That was a long time!

The book was put in the back burner on and off. In the meantime, I asked different religious I knew to go over the text, and was given some wonderfully helpful input, and even correction. One of them was Fr. James Downey, O.S.B., of happy memory. In fact, he had been an officer of the Institute on Religious Life. When I told him about my predicament of not finding the right illustrator, he suggested I just use photography. That certainly was not what I had in mind for the book! A couple of years later, though, I gave in and decided to go ahead and use photographs. At least the text would be made available. So, as a first step, I contacted a Benedictine superior I knew and asked him if I could have a photograph of his monks. The unequivocal answer came back immediately: “No, … but I know an illustrator.” And that was Michaela Harrison. God’s ways are not our ways, nor his timing, ours. She would have been too young when I first drafted the text. Michaela took my sketches and ideas and copiously multiplied and expanded on them. Her drawings just carry this unction. I could not be happier.

Let’s talk a little bit about the text. You mentioned you deliberately wrote in a methodical, straightforward way.

I didn’t want to make it age-specific. Over the past decades, or even the last century or so, we have gradually dumbed down the human mind by underestimating the capabilities of children, their capacity to understand and internalize concepts and ideas. Things have to be made “digestible.” And the threshold has been pushed further and further to the point where now we think of 30-year olds as being “young” adults! That certainly was not the case for most of the history of humanity. St. Alphonsus Liguori attended Law School at age 16, and that wasn’t anything extraordinary for his time.

I didn’t want to make it age-specific. Over the past decades, or even the last century or so, we have gradually dumbed down the human mind by underestimating the capabilities of children, their capacity to understand and internalize concepts and ideas. Things have to be made “digestible.” And the threshold has been pushed further and further to the point where now we think of 30-year olds as being “young” adults! That certainly was not the case for most of the history of humanity. St. Alphonsus Liguori attended Law School at age 16, and that wasn’t anything extraordinary for his time.

So the text is simple and very methodical. It begins by discussing what vocation is in general, and then it goes into the religious calling and how someone goes about becoming a religious—from discernment, through postulancy, novitiate, to profession. In this context, I have a section on the importance of the religious habit, and another on the vows, or three evangelical counsels. Then the main text closes with an explanation of “what religious do,” that is, what they are about, how they go about their day. Here I explain the contemplative and active life. Finally, there is an explanation of the priesthood and the difference between a religious and a secular priest.

And how about your original intention of writing about the main religious orders?

I may someday get to that, if I ever have the time. But for now, at the end of the book I have a substantial appendix on certain religious orders—those that are represented in the several illustrations in the book. Here I provide some of the history of the order, a little of the charism, and mention a saint of that order, mostly the founder or foundress. And I was blessed to be able to have a faithful member of each order review the pertinent text. Even the Carthusians in Vermont were good enough to do that!

How can people get Of Bells and Cells?

It is carried by EWTN Religious Catalogue and by Vianney Vocations. Or people can simply search online, on Amazon or other outlets. There is also a Czech version of the book, as well as French and Portuguese versions. People can visit www.stbonosabooks.com for the titles of these translated versions and then search for them online. There’s a Spanish translation in the making but I do not know when that will come out.

Any parting thoughts?

I should say that the reason I was touched so deeply by the lack of knowledge of that teenage girl was that I too had known nothing about religious orders or saints. In fact, I knew nothing about Catholicism. I practiced no religion until I was about her age. And even though I went to Catholic schools, this was in the 70s and 80s, and I had learned nothing of any substance. It was only years later that life led us to begin discovering the treasures of the Faith, and this was largely through reading the lives of the saints and church history. And then we started frequenting a Carmelite monastery for Mass. We benefited so much from the nuns’ prayers, and also from the short little counsels at the turn, or the parlors through the grill. A whole new, rich, life-filled world opened up to my soul.

Christendom was built upon religious life in so many ways, but I need not preach to the crowd. Two parting thoughts, though. When Roman civilization was crumbling, St Benedict went to seek God in a cave. Then St. Gregory the Great picked up the thread of civilization and Benedictines built Christendom. At the height of the Terror in France, it was the martyrdom of the Carmelites of Compiègne that brought the carnage to an abrupt end, in ten days. And so forth throughout history.

Religious life, particularly contemplative, is the hidden lungs of Christian civilization. I hope this little book does a little something to increase awareness of this necessary treasure.