St. Benedict has a lot to say regarding our attitude of reverential awe and charitable respect shown to God and towards our fellow human beings.

St. Benedict has a lot to say regarding our attitude of reverential awe and charitable respect shown to God and towards our fellow human beings.

For example, he begins Chapter 4, on “Good Works” with “First of all, love the Lord God with your whole heart, your whole soul and all your strength, and love your neighbor as yourself” (Matt 22:37; Mk 12:30; Lk 10:27).

Loving God is the starting point of all that we do and all whom we meet in our Christian walk. Even strangers, the poor and pilgrims are to be “welcomed as Christ” (RB 53:1). As the late Abbot Georg Holzherr, OSB, of our grandmother house put it: “Genuine hospitality especially towards the poor and pilgrims, is a hallmark of a truly humane culture in dealing with others, and it is certainly a theme that stands out in the Bible.” This is especially true for monastics, and by way of extension, the Oblates: “They should each try to show respect to the other (Rom 12:10) (in RB 63:17).

Reverence at the Divine Office, the Work of God, merits an especially important place in the chapters on Prayer: “As soon as the cantor begins to sing ‘Glory be to the Father,’ let all the monks rise from their seats in honor and reverence for the Holy Trinity” (RB 9:7).

Liturgical reading is to be “done with humility, seriousness and reverence” (RB 47:4). “After the Work of God, all should leave in complete silence and with reverence for God, so that a brother who may wish to pray alone will not be disturbed by the insensitivity of another” (RB 52:2,3). Even monks traveling on mission “are to perform the Work of God where they are, and kneel out of reverence for God” (RB 50:3).

Liturgical reading is to be “done with humility, seriousness and reverence” (RB 47:4). “After the Work of God, all should leave in complete silence and with reverence for God, so that a brother who may wish to pray alone will not be disturbed by the insensitivity of another” (RB 52:2,3). Even monks traveling on mission “are to perform the Work of God where they are, and kneel out of reverence for God” (RB 50:3).

Essentially, all aspects of monastic life are to be done with a spirit of cheerful humility towards each other. “The younger monks, then, must respect their seniors, and the seniors must love their juniors” (RB 63:10). When praying the Liturgy and addressing God, they do

so with fearful but loving awe, as when the Abbot “reads from the Gospels while all the monks stand with respect and awe. (RB 11:9).

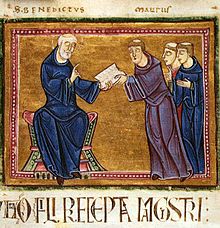

St. Benedict had an excellent grasp of the Holy Scriptures, and therefore he was able to craft his rule, sentence by sentence, with the goal of forming holy monks into cohesive groups of twelve monastics. Many of his disciples were illiterate rustics who became trained by the Holy Rule until they were ready to go out to evangelize their parts of the world by founding more and more monasteries. Eventually there were about 1,400 monasteries scattered all over Europe.

With attention to detail, the reference to pure prayer speaks to the whole person—body and soul. “ Let us consider, then, how we ought to behave in the presence of God and his angels, and let us stand to sing the psalms in such a way that our minds are in harmony with our voices” (RB 19:6-7). With keen awareness of human behavior, he writes, “ Whenever we want to ask some favor of a powerful man, we do it humbly and respectfully, for fear of presumption. How much more important, then, to lay our petitions before the Lord God of all things with the utmost humility and sincere devotion. We must know that God regards our purity of heart and tears of compunction, not our many words” (RB 20:1-3).

With attention to detail, the reference to pure prayer speaks to the whole person—body and soul. “ Let us consider, then, how we ought to behave in the presence of God and his angels, and let us stand to sing the psalms in such a way that our minds are in harmony with our voices” (RB 19:6-7). With keen awareness of human behavior, he writes, “ Whenever we want to ask some favor of a powerful man, we do it humbly and respectfully, for fear of presumption. How much more important, then, to lay our petitions before the Lord God of all things with the utmost humility and sincere devotion. We must know that God regards our purity of heart and tears of compunction, not our many words” (RB 20:1-3).

This kind of respectful harmony flows out to our contact with holy superiors and confreres in such appealing phrases as “…the disciples’ obedience must be given gladly, for God loves a cheerful giver” (2 Cor 9:7) (RB 5:16).

Respecting human frailties, he gently advises his followers with such phrases as, “This, then, is the good zeal which monks must foster with fervent love: They should each try to be the first to show respect to the other (Rom 12:10), supporting with the greatest patience one another’s weaknesses of body or behavior” (RB 72:3-5).

Brother Daniel Sokol, OSB, is a Benedictine monk at Prince of Peace Abbey in Oceanside, California.

Brother Daniel Sokol, OSB, is a Benedictine monk at Prince of Peace Abbey in Oceanside, California.